Pet bereavement - grief that is not always acknowledged.

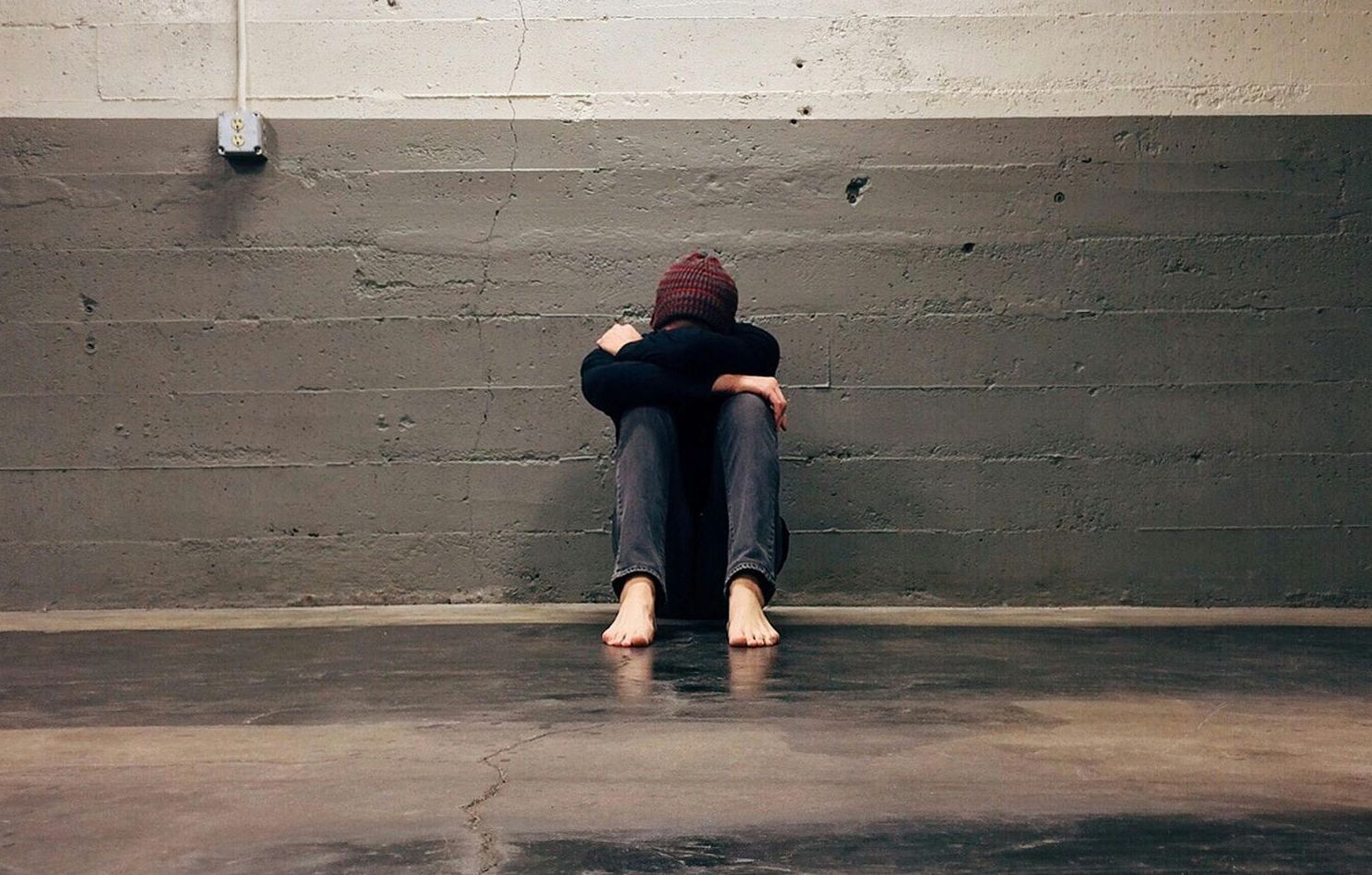

Losing a beloved pet can be one of the most heartbreaking experiences a person can go through. Whether the loss is sudden—perhaps from an accident—or comes after a long illness or the slow effects of ageing, it can bring with it a deep emotional

pain. When a pet's health declines over time, there are often incredibly tough decisions to make. Questions about treatments, quality of life, and knowing when it’s time to say goodbye can weigh heavily on your heart.

The bond we share with our pets is powerful. They’re our companions, our comfort, and often feel like part of the family. Research has long shown the mental and emotional benefits of having a pet—but sadly, grief after pet loss isn’t always

acknowledged in the same way as other kinds of grief. Many people feel hesitant or even embarrassed to talk about how deeply they’re hurting, especially if others don't understand.

In many workplaces, for example, there is often little or no recognition of pet loss. People are often expected to just carry on, using personal leave or returning to work as if nothing has happened. This lack of support can leave grieving pet owners feeling isolated and dismissed.

When grief isn’t recognised or validated by others, it’s known as disenfranchised grief (Cordaro, 2012). Unfortunately, this can be common after losing a pet. There’s often subtle pressure to “get over it” quickly or to adopt a new pet right away—as if the deep connection and love you shared can simply be replaced. Anyone who has loved and lost a pet knows that grief doesn’t work like that.

The intensity of grief depends on your relationship with your pet and the circumstances around their passing. Some people feel immense sorrow and even guilt, especially if they had to make the painful decision to euthanise. Others may experience overwhelming loss and sadness when their pet was like a child or sibling within the family. The feelings associated with the loss of a pet are real—and they matter.

If you’re grieving the loss of a pet, know that you are not alone. Joining a support group with others who understand this unique kind of loss can be a powerful step toward healing. Talking with others who have walked a similar path can help validate your experience and remind you that your grief is valid, no matter what others may say.

Counselling4Loss offers group support specifically for those grieving a beloved pet. If you’d like a safe and compassionate space to mourn and remember, we encourage you to reach out.

References

Cordaro, M. (2012). Pet loss and disenfranchised grief: Implications for mental health counselling practice. Journal of Mental Health Counselling, 34(4), 283-294.